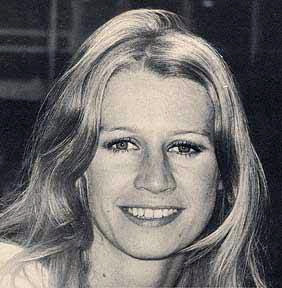

Though she sang with one of the best one-shot bands on the UK’s fertile late 60s / early 70s scene, and released a much-admired solo LP soon afterwards, Linda Hoyle has become something of an enigma. I am delighted to offer here the fullest interview she has ever given, covering her personal and musical background, her experiences with Affinity, how the Pieces Of Me LP came about, and why she disappeared from view so soon after its release in late 1971.

How did Pieces Of Me evolve?

What happened after the release of Pieces Of Me?

Pieces Of Me and various recordings by Affinity can be bought via http://www.angelair.co.uk

Was your background musical?

I grew up in Chiswick, West London, and both my parents were musical. My mum played the piano and my dad played ukulele, and they had a large collection of jazz 78s, so all my heroes as I grew up were jazz musicians. My sister Wendy and I were both avid ukulele players as children, and eventually progressed to playing guitars. Wendy was more instinctively musical than me, and could harmonise naturally. As children we sang together constantly, and were greatly encouraged by our parents.

What were your early musical influences?

What were your early musical influences?

Until I became a rebellious teenager I played my parents’ record collection to death. It largely consisted of jazz and blues, which meant I was a bit of a snob about rock and roll (until I heard Elvis Presley, and how well the Everly Brothers could sing!). By the early 60s I was interested in R&B, and used to go to see The Rolling Stones at The Crawdaddy Club in Richmond and Eel Pie Island – they played the sort of raw R&B I liked. But the biggest influence on my whole career as a singer was Billie Holliday, whom I first heard when I was about 16, in 1962 or so. No one really knew about her in the UK at the time, and I was staggered by how different she was to the blues singers I’d been listening to, like Mildred Bailey. I worked out that she was singing a long way behind the beat and flattening the melodies so she could sing across them and avoid going high and low, because her range wasn’t large. She also had wonderful diction, which made her music very sensual, like being kissed. At Teacher Training College I used to sing blues songs in clubs, accompanying myself on ukulele or guitar (blues was considered folk in those days), but I always knew I’d melt as soon as I found someone who could play interesting chords on a piano behind me, so I could throw away my guitar.

When did you decide to embark on a singing career?

After Chiswick County Grammar School I spent a year working as a medical technician before training to become an English and art teacher for three years. When I was 19 I got engaged to a guy who was at Sussex University, so I used to spend my whole time down there. One day I saw these three guys playing jazz in the common room – Lynton Naiff on piano, Nick Nicholas (who’s now been my husband for nearly 40 years!) on bass and Mo Foster on drums. I spontaneously sang an old song with them (called I Thought About You), but it wasn’t with any intention of joining them. Back in London I had a teaching job all lined up, when out of the blue one day in the spring of 1967 I got a call from Lynton, saying that the group had been offered a summer season in Bognor Regis, but needed a singer, and was I interested? The answer was yes – much to my father’s horror – and that’s how it all started.

Was that the beginning of Affinity?

I suppose so, though we only really played jazz standards on that summer engagement. After it the guys regrouped as Ice (with a singer called Glyn James) and released a couple of 45s on Decca, while I returned to London to finish college. By the summer of 1968 Lynton had rented a bungalow in Brighton and bought a Hammond organ, and we decided to have a proper go at forming a band. We found our guitarist, Mike Jopp, through an ad in Melody Maker, and rehearsed hard until we had a set together. Lynton was always the driving force behind Affinity, the dynamo. He’s a difficult but brilliant guy, an incredible musician and mathematician, and was gorgeous to look at, half-Jewish and half-Arab. He and I got together after I’d got my teaching diploma, and he was the one who moved me towards modern jazz. We were a couple for most of the time I was with Affinity, in fact.

We were talent-spotted by a guy named Andrew Cameron Miller, who trawled clubs looking for talent, I think. He was in business with a guy named Jim Carter-Fea, who ran three of the hippest clubs in London – The Revolution, The Speakeasy and Blaise’s. Jim became our manager for a short time, and gave us a residency at The Revolution, which was always rammed. We played our first gig there on October 5th 1968. I remember seeing John Lennon and Paul McCartney in the audience once, and Stevie Wonder jammed with us on harmonica one amazing night. We weren’t especially flamboyant as performers, as we always tried to be as musical as possible, but I did trawl through Brighton junk shops looking for turn-of the-century velvet and lace clothes to wear onstage. The problem was, they were so fragile that they only lasted a few nights each!

How did you become involved with Ronnie Scott?

Jim Carter-Fea wasn’t the right manager for us, and after a while Mo played a demo we’d made to Ronnie Scott, who was branching into artist management, with his partners Pete King, Jimmy Parsons and Hugh ‘Chips’ Chipperfield. I think Ronnie thought rock might be more lucrative than jazz, so he started a company called Ronnie Scott Enterprises and soon had a hit with Gun. Ronnie redesigned the upstairs of his club so as to attract a younger crowd. He got Roger Dean to design the furniture, so it ended up looking like a surreal latex farm run by Salvador Dali. God knows what it must have cost! We played there a lot, and it really felt like home.

What was the atmosphere like at Ronnie Scott’s?

It was wonderful, with this incredible, Dickensian cast of characters – Tiny the bouncer (who was, of course, enormous), Chuck the barman (who had a battered trumpet and dreamed of being a star himself), and Albert the heavy (who once told me in all seriousness to inform him if anyone gave me trouble, so he could kneecap them). It was the place for jazz musicians to congregate, so all the players we respected hung out there, people who really knew their stuff. In those days visiting American stars would use pick-up bands, because they couldn’t afford to bring over their own people, and Ronnie Scott’s was where they would be drawn from. There was an assumption that these musicians we held in awe were wealthy, so it was always a shock to find that they were broke; I remember Harold McNair sleeping on our floor after one gig. We didn’t back other people ourselves, though I remember Stan Getz asking us to go on tour as his band. Another act Ronnie managed was Igginbottom - I remember being amazed by their guitarist, Allan Holdsworth. He used to practise on a really cheap guitar, and he told me the reason was that it would guarantee he'd sound better when he played with his real instrument in front of an audience!

Who were your favourite contemporary singers and players?

|

| Disc & Music Echo, June 13th 1970 |

I had a bit of a crush on Julie Driscoll – she was so beautiful, and had such an independent style. Lynton and I frequently went to see her and Brian Auger live, usually in a pub somewhere in North London, where we’d sit in the front (and I never usually did that!). They swung amazingly, and Lynton was transfixed by Auger’s Hammond organ with Leslie speakers. He lusted after them, and eventually bought them from him! Aretha Franklin, of course, was like something from another planet, and I loved all the soul guys – Marvin Gaye, James Brown and so on. I was fascinated by the way they used their voices rhythmically rather than melodically, to the point that the actual words they sang didn’t much matter. Terry Reid was terrific, with a high-pitched male style that was adopted by Robert Plant later on. And I loved Janis Joplin, of course – in my heart I have always fundamentally been an improviser, but it was very hard to get away with that and be commercial in the late 60s. She was one of the very few that managed it. I thought Laura Nyro was wonderful too – so personal and distinctive, certainly not the sort of songs you could dance to. As for rock, I liked most things that were big, loud and not folky! I loved the Stones, the way that the whole was the greater than the sum of their parts, and liked The Yardbirds. And Cream were wonderful, with that terrific rhythm section. Jimi Hendrix, of course, seemed superhuman, like he hardly existed in flesh. He consistently achieved the thing that most musicians aspire to but only achieve fleetingly – to become as one with their instrument. I think I saw him live once, but these experiences become like dreams after a while. I should add that my tastes have broadened a lot since those days, probably because I’m not competing anymore, so there’s no envy clouding my judgment. It took me a long time to acknowledge that, no matter what I did, there would always be dozens of people who could do it better!

What was your lifestyle with Affinity like?

We worked incredibly hard, but never had any money. On a typical night we might get £20 to split between us, and that had to cover our equipment and travel as well as living expenses. My main memory is of always being hungry – we used to steal food from the kitchens at Ronnie Scott’s, and Mo Foster ended up in hospital with malnutrition at one point. Because we were so poor, we didn’t have the equipment we needed, so when there was a fire at Ronnie Scott’s and all our gear went up in smoke, it was a disaster because it wasn’t insured. Lynton’s dad ran a music shop in Soho and had his own line of cheap amps called Impact, which we used in the early days. I remember seeing all of Terry Reid’s amazing equipment being set up at one gig, and thinking: that’s what I need!

I’ve read that you had to have a throat operation in 1969.

That’s right – as I never had a monitor, I could never hear myself sing. As a result I pushed my voice too hard to get volume over the band, and inevitably developed nodes on my vocal cords. I had to go off to see a specialist in Harley Street, had an operation and was forbidden from speaking for a whole month (which was incredibly difficult!). Ronnie and his right-hand man Pete King were always very protective of me, and found me a classical singing teacher called Mable Coran, who changed everything by showing me how to sing powerfully from my stomach, rather than screaming my head off. In the meantime, the band loyally played gigs instrumentally (some of the music they made in my absence has since come out on CD).

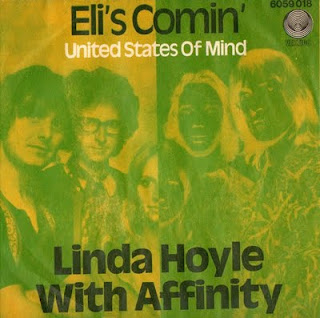

It was all arranged through Ronnie Scott Enterprises – the deal was actually with Philips, and it was their decision to put us on their new Vertigo label. We nearly fell over when we got an advance of £2000 (which we promptly spent on equipment)! Phillips put us together with one of their staff producers, John Anthony, who was a lovely guy. They really let us loose in the studio, but I was only partially satisfied with the finished record. Like most musicians, I tend to hear the mistakes when listening to recordings of myself…

Affinity was one of the few artists that John Paul Jones arranged for while he was in Led Zeppelin. Do you remember working with him?

Yes – I clearly remember standing with him in the Philips studio in Marble Arch. He was pleasant, sober and businesslike – no mucking about, just getting on with the job. He got on well with Lynton, who was also very interested in arranging. There was no sense of gawping at him because he was a star – at that time there was much less of a division between musicians, people just milled about the scene. People who could actually play well respected each other, irrespective of their level of success, and there was a sense of wanting to learn from one another, as if we were all trying to make one big pudding!

Is it you on the Affinity cover?

What happened after the album came out?

Is it you on the Affinity cover?

No, it’s not – it’s a model that supposedly looked like me. The original idea was that Roger Dean should design the sleeve, but I foolishly nixed that, because I didn’t properly understand what was being proposed. The finished design is quite enigmatic, I suppose, but it suggests we were more airy-fairy than we actually were.

|

| Sounds, November 14th 1970 |

We promoted it by having a whole episode of The Old Grey Whistle Test devoted to us, though I suspect that’s now lost. I remember having to have a clothes budget for the taping, and several changes of costume! By the end of 1970 I was exhausted by all the touring. I’m not especially tough physically, and decided I just couldn’t go on travelling and living like that. In addition, Lynton and I had split up and I was seeing someone else, which added another problem to being in the band, so I left at the start of 1971.

|

| http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7wvry4hKspo&feature=channel_video_title |

Didn’t you sing a Shredded What jingle in 1970 or so?

Yes, and thanks for reminding me! It went ‘There are two men in my life /

To one I am a mother /

To the other I’m a wife /

And I give them both the best

/ In natural Shredded Wheat.’ I even sang it live on the Michael Parkinson show once, and shared a dressing room with Shelley Winters. That was fairly surreal. Actually, I shouldn’t be too rude about it – I made more money out of residuals for that advert than I did in all my time with Affinity or as a solo singer. By the way, there’s a weird LP of jingles floating around out there that includes it.

There’s also a rumour that you sang on the Get Carter soundtrack.

Sadly not – I definitely didn't sing on that. I expect my bank manager would have been happier if it had been the case!

|

| Disc & Music Echo, February 6th 1971 |

There’s also a rumour that you sang on the Get Carter soundtrack.

Sadly not – I definitely didn't sing on that. I expect my bank manager would have been happier if it had been the case!

How did Pieces Of Me evolve?

Ronnie Scott and Pete King were still my managers, and encouraged me to continue writing and singing, as well as to take drama classes. They also managed Karl Jenkins, and eventually suggested he and I write together. Pieces Of Me was put together in his tiny flat in Portobello over the course of 1971. We’d sit side by side at the piano, as he improvised melodies and I improvised words. We threw a lot away, and often took breaks in the pub, but had soon come up with enough songs for an album. It was produced by Pete King, and recorded in about three days flat, with various members of Nucleus, including Chris Spedding, who was a great guitarist and a very odd character who always wore sunglasses (even in bed at night). It was the first time Karl had arranged for an orchestra, and his arrangements used phrases that he still uses now – listen to For My Darling and his Adiemus, for example.

What do you make of the album today?

The main point I’d make about it is that it was exactly what its title says – little pieces of the different things that had influenced or touched me. I think Ronnie and Pete understood that I had to get all of that out of my system before perhaps progressing to a more unified second solo record. So Barrelhouse Music is a tribute of sorts to the music I was listening to growing up, and Mortie Mole (not Marty Mole, that was a typo) is all about various experiences I’d had and people I knew, such as Lynton Naiff, Pete King, Ronnie Scott, my sister and my husband. Morton is his middle name, and though some might consider it a little kitsch, the song still has an emotional resonance for me. I think the most under-rated song on the record is Hymn To Valerie Solanas. I was fascinated by her S.C.U.M. Manifesto, and though I wasn’t a radical feminist myself, it struck a strong chord with me because the music business was terribly sexist and misogynistic, and I had some very nasty near-escapes with men we’d encountered.

|

| NME, November 6th 1971 (written by co-manager Jimmy Parsons...) |

How would you summarise your experience as a girl in the music industry in those days?

It was a man’s world, and the sooner you learned that and worked out how to deal with it, the better. I went out of my way not to be perceived as vulnerable, and never played the damsel. I had a big mouth anyway, so never put up with being patronised. In fact, far from playing the girly card, I always gave as good as I got. I was quite a tough cookie, and regarded men as potential predators, so I absorbed some of their worst characteristics in order to make them back off. In the period leading up to my joining Affinity, I had almost all my hair cropped off and took to wearing a North African desert army uniform and desert boots. I was quite aggressive in those days, and swore like a navvy. I insisted on doing my equal share of lugging the gear in and out of clubs, and before long my muscles were pretty good – and I wasn’t afraid of using them. I can certainly remember hitting people over the head with my microphone! Another point worth making is that lots of girls in the 60s saw the pill as some sort of miracle – it was a contraceptive, it made your boobs bigger and improved your skin! – so went stampeding off to the doctor to get it. But the corollary was that a lot of men thought that the pill made it okay to be sexually pushy with women, as if to say “You can’t get pregnant, so what’s your problem?”

Do you think it’s easier or harder to be a female performer today?

Funnily enough, I think it’s probably harder. Of course, there were a lot of sexist attitudes back then that wouldn’t be tolerated now, and Western women have got far greater legal recognition over the past 40 years or so. But I also think the media has sexualized young women to the point of pornography since then; there has been a tendency towards them being not just objects, but revealed objects, and it’s mostly men driving them to present themselves that way. Women need to realise that, as sure as death lies at the end of the cigarette industry, it’s men making money out of them that lies at the end of the music industry. It really saddens me to see such an amazingly talented but damaged person like Amy Winehouse having breast enlargement surgery, for example.

|

| Disc & Music Echo, December 4th 1971 |

|

| Record Mirror, December 18th 1971 |

|

| Sounds, January 15th 1972 |

What happened after the release of Pieces Of Me?

I fell in love with Nick around the time the album was made, and we decided to move to Canada in the autumn of 1971, just before it was released. As a result, I didn’t play a single solo show to promote it. I flew back to appear on The Old Grey Whistle Test in April 1972 (singing Marty Mole, Black Crow and Paper Tulips), and that footage is floating around out there somewhere. On the same trip I travelled to Germany to play a show with Soft Machine, the idea being that I would sing a few of my songs as well as with them – but the audience was not happy about them having a singer up front, and booed and heckled until I gave up and left the stage. Moving to Canada was a tough decision, as I loved recording, and I think I could have gone on to have a singing career – at the time there were very few women doing the sort of things I was (that’s all changed now, of course).

What are you doing these days?

I’m just about to have my textbook on art therapy published (under my married name, Linda Nicholas). It’s called Drawing Out The Self, and has taken me many years. My next book is about the perception of the interior of the body, and will be a little more controversial. I still sing, mostly jazz, and only when the setting is nearby and relaxed. I often visit Mo Foster when I am in the UK, and Affinity has come together several times in the last five years, though Lynton has stayed out of it. There is no doubt that they were a terrific band, and swung like the clappers on occasions. Now and again I am in touch with Karl, but (as I’m sure you know) he’s now mighty rich and famous. It’s very gratifying to know that people still enjoy my recordings, so thank you.

No comments:

Post a Comment